Another July 4th has passed, and the myths surrounding that popularly celebrated national holiday seem as potent as ever on the 239th anniversary of the American colonies’ war for independence from Great Britain, even among those who should know better. Fortunately, there are a small number of honest and dedicated historians out there who are not afraid to delve deeper into the actual historical record and expose the so-called “American Revolutionary War” for what it actually was, and the picture they paint is the antithesis of everything we’ve been conditioned to believe about the founding of our ‘Republic’. Most prominent among these New Age historians is Gerald Horne, the Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Houston.

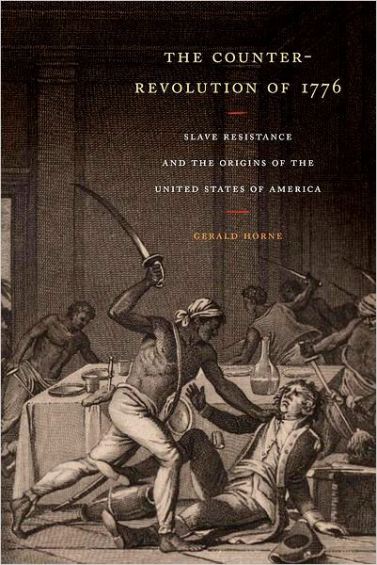

Gerald Horne’s groundbreaking new book, The Counter-Revolution of 1776: slave resistance and the founding of the United States of America, was published by New York University Press in April of last year and was slept on by most of the mainstream media and all but ignored in even the more liberal outlets like the Huffington Post. This is due to the fact that understanding the war for American Independence through such a radically different lens than the one we’re used to uproots many of the nationalist and patriotic notions most still have about this country, and would undoubtedly lead some to question the very legitimacy of the United States of America. Horne, whose extensive research includes viewing and reading the actual records of the former colonial legislatures as well as the letters and opinions of rebels and Loyalists alike, demonstrates without a shadow of a doubt to any sensible reader “that preserving slavery was an impelling motivation for colonial secession” and that “because slaves (and indigenous people) were perceived as a subversive element during the war, the rebel victory cast them in the longstanding role of ‘intense enemies’ of the state.” Though his conclusion is a radical one, it is supported overwhelmingly by documentary evidence.

Gerald Horne’s groundbreaking new book, The Counter-Revolution of 1776: slave resistance and the founding of the United States of America, was published by New York University Press in April of last year and was slept on by most of the mainstream media and all but ignored in even the more liberal outlets like the Huffington Post. This is due to the fact that understanding the war for American Independence through such a radically different lens than the one we’re used to uproots many of the nationalist and patriotic notions most still have about this country, and would undoubtedly lead some to question the very legitimacy of the United States of America. Horne, whose extensive research includes viewing and reading the actual records of the former colonial legislatures as well as the letters and opinions of rebels and Loyalists alike, demonstrates without a shadow of a doubt to any sensible reader “that preserving slavery was an impelling motivation for colonial secession” and that “because slaves (and indigenous people) were perceived as a subversive element during the war, the rebel victory cast them in the longstanding role of ‘intense enemies’ of the state.” Though his conclusion is a radical one, it is supported overwhelmingly by documentary evidence.

Conflict between the Royal Crown of Great Britain and the plantation-owning elite of her settler colonial class in the western hemisphere regarding the theft of African bodies to be held in bondage was present almost from the beginning. Neither was opposed to the immensely profitable enterprise, far from it! The conflict was over who should and should not be able to maximally profit from it. During the 16th century, Great Britain had granted the Royal African Company sole proprietorship over what was called the transatlantic slave trade, and harsh punishments were ostensibly to be handed down to those who thwarted this monopoly. However, the desire for chattel – forced, enslaved labor – was so immense among the “New World” settlers that a merchant class of private, illegal traders conducted their own sort of black market, kidnapping black bodies directly from Africa and bringing them over to the mainland colonies and Caribbean Islands. This was much to the consternation of the British Mother country, for the illegal trade being carried out by these merchants was undermining the officially sanctioned Royal African Company by cutting deeply into its profits. The conflict appeared to subside for a brief time with the so-called “glorious revolution” in England of 1688, which essentially ran the Royal African Company into the ground when it came to being a major player in the slavery enterprise. With the R.A.C.’s power diminished, the slave trade thrived as never before, with an entire class of elites making themselves rich off the kidnapping and selling of stolen African bodies without the necessary approval of the Crown. Even though the R.A.C. was out of the picture, however, the power Great Britain held when it came to its progeny’s cruel but profitable enterprise was not eliminated by any means. It still collected immense profits from the merchants’ and settlers’ slavery-based economy in the form of Tariffs, Taxes and various other regulations, all of which angered the settler elite and proved to be a determinative factor in their later decision to rebel.

The importation of enslaved Africans was not without serious repercussions. For starters, Africans had demonstrated time and time again that they were not going to submit to a subordinate position without putting up a formidable amount of resistance. Nor were the Indigenous going to give up the land they’d inhabited since time immemorial without a long, brooding fight. Slavery was a double-edged sword in a way, though we are not accustomed to viewing it that way. While more slaves generate more profits through unpaid labor, it is also true that those who make up this brutalized labor force are likely to strike their oppressor when an opportune moment arises, as demonstrated by numerous slave rebellions, insurrections, and intentional poisonings that took place. This kept the settlers in a constant state of panic and fear, and put Britain in the awkward position of trying to limit the amount of potential insurrectionists brought in to the New England colonies while also ensuring that the slavery-based economy continued to grow. Exacerbating these problems ten-fold were the rival European colonial powers, France and Spain, who were each a constant thorn in the side of London. Spain, after all, was in complete control of the Florida peninsula, and from its base at St. Augustine carried out a policy of providing sanctuary for escaped Africans as well as the Indigenous, supplying them with arms and weaponry so that they were able to mete out their revenge on the colonists further north. This reached a climax with the French and Indian War in the 1750’s-’60’s, which saw Paris ally itself with Native American Indian tribes in opposition to Britain’s American colonies. And since the New England settlers were reluctant to participate in actually fighting to defend their colonies (instead relying almost solely on Mother Britain), Britain made the decision to enlist a number of Africans from the Caribbean in the British Red Coats during the war. This became a huge source of antagonism with the New England colonists, whose blood boiled with rage upon seeing those who they were conditioned to see as their divinely appointed slaves in a status equal if not superior to their own. The settlers also took issue with being taxed to pay for the defense of their colonies, developing a sense of entitlement to the whole North American continent that would become a hallmark of their republic upon establishing independence.

By the end of the Seven Years’ War, London had succeeded in repelling the French and the Indigenous tribes for the time being. It also succeeded in ousting Spain from Florida as a condition for the return of Cuba. The biggest losers of this war were no doubt both the Africans and the Indigenous, whose base of rebellion in St. Augustine, Florida was eliminated. From 1763 onward, according to a contemporary witness, “exterminating Indians became an act of patriotism.” Incredibly ironic is the fact that Great Britain, in succeeding and winning the war, also lost in the long-run. Though the Red Coats had rescued the British colonies from annihilation, they’d also laid the groundwork for these very same colonies to stab them in the back a decade later. At the heart of the conflict was the fact that London, after fighting and winning a very deadly and costly war defending the colonies, was seeking to prevent as much as possible for the time being having to involve itself in any further wars with Indigenous tribes. It was also determined not to encourage further revolts or acts of mutiny on the part of rebellious enslaved Africans, which would be exceedingly difficult to do as long as they continued being imported in unchecked numbers. The Crown had good reason to worry, as the Indigenous peoples no longer had any illusions as to the ultimate goal of London’s colonial-expansionist project, as evidenced in the tone of a letter sent from London to the Governor of Georgia. The letter, dated March 16, 1763, states that, despite Spain no longer occupying the Florida peninsula, “the French and Spaniards in Florida & Louisiana have long, and too successfully inculated the idea amongst the Indians, that the English entertain a settled Design of extirpating the whole Indian race, with a view to possess & enjoy their lands.” [Horne, Gerald. The Counter-revolution of 1776: slave resistance and the origins of the United States of America. Page 195] Of course it wasn’t necessary for the Spanish or French to “inculate” any such ideas into the heads of the Indigenous peoples at all, for they’d had over a century to observe and learn the true character of the colonialists, and had come to the rightful conclusion that the settlers would stop at nothing until all the Natives were either landless or exterminated. Now, with the Seven Years’ War ended, the settlers were more determined than ever to speed up the process of “Indian removal” from lands even further west of the colonies, “with the rapt desire to enslave Africans to toil on this very same land.” [Horne, 185.]

The sense of a unifying cause among the white settler population that caused them to loathe Great Britain was not formed overnight. In fact, in the earliest days of colonization of the North American continent the various ethnicies and religious sects of Europe were constantly at each other’s throats. Nowhere was this hostility more pronounced than in the shared hatred Protestant England and Roman Catholic Spain had for each other. “Whiteness” was able to become a unifier only in the context of enslavement of Africans and genocide of the Indigenous. To put it another way, the concept of whiteness became a great unifier for people of vastly different origins in the face of fierce resistance shown by Africans, who refused to accept being enslaved, and indigenous American Indians, who refused to be eliminated. These two groups violently resisted the even more brutal violence that was being inflicted on them, every step of the way. (*) Had it not been for the new all-inclusive definition of whiteness – one that included among others the English, Dutch, Irish and French – many of these “whites” would have had little reason to fight a war which served to benefit mainly a rich, wealthy class of property-owning elites. Considering how, only a few years prior to the rebellion against Britain, a staggering 44% of all the wealth being generated in the New England colonies was accumulated by just 1% of the property-owing population, it’s difficult to understand without the racial context how a largely impoverished population of white indentured servants could find common cause with the relatively small plantation-owning class. Being offered the privilege of “whiteness” however was an offer the average poor European migrant couldn’t resist. Whiteness became a tool of the ruling class to instill in the rest of the settler population a sense of racial superiority that allowed them to believe that, no matter how humble their origins, they were still of a superior racial stock than that of the non-white Africans and Indigenous Indians. One of the most demonstrative examples of how this process played out is the decision made by the elite in the aftermath of Bacon’s Rebellion in 1675, when lower-class white men were suddenly “given guns and allowed a certain amount of freedom and control over black bodies, instilling in them a sense of importance and ownership they had not felt when they were simply laborers.” A century later, in the build-up to the American Revolutionary War, a prominent anti-London “patriot” and slave-owner named Christopher Gadsden played a crucial role in consolidating this cross-class white racial solidarity. It was Gadsden’s assertion “that the prospect of slave insurrection should remind the white poor of their presumed identity of interests with their racial brethren, who happened to be filthily wealthy planters and merchants.” [Horne, 199.]

Finally, whatever amount of reverence the New England settlers had left for Britain was irrevocably tarnished when a heretofore inconceivable concept – abolition – became a point of serious discussion among certain echelons of British society. What began as a small fringe movement suddenly reached a feverish pitch in 1772 with a decision handed down by Lord Mansfield in the infamous Somerset v. Stewart case in England, which effectively outlawed slavery in the British mainland. Though this decision did not address slavery as it related to Britain’s overseas colonies, the elite plantation owners and slave merchants in North America concluded that the decision in the case would eventually lead to exactly that. Immediately following this verdict, which proved to be a groundbreaking decision, colonialists in the American colonies took to newspapers and magazines to express bitterness and outrage over the ruling, with many writers writing without a trace of irony that Great Britain was treating them – the slave-holding settlers – as if they were slaves! One Richard Henry Lee even opined that the plight of the white settlers was akin to being held in “Egyptian bondage.” [Horne, 217.] Leading abolitionist voices coming out of London hardly offered any words to assuage these overblown fears. In fact, the shrill, hypocritical protests of the slave-holding settlers immensely contributed to the ascendant political awareness of London’s growing abolitionist community and the radicalization of more than a few of them. One of the most radical denouncements of New England slavery appeared in a London abolitionist pamphlet the same year as the Somerset verdict titled Britannia Libera or a Defense of the Free State of Man in England against the Claim of Any Man There as a Slave; Inscribed and Submitted to the Jurisconulti and the Free People of England. Within the pamphlet it is predicted that a time would justly come “when the blacks of the southern colonies on the continent of America shall be numerous enough to throw off at once the yoke of tyranny to revenge their wrongs in the blood of their oppressors and carry terror and destruction to the more northern settlements” and spreading to the Caribbean Islands a “merited carnage” which “may end to the disadvantage of the whites.” [Horne, p. 217-218]

With London now preventing the settlers from expanding westward, and levying more burdensome taxes on the importation of enslaved African laborers (to avoid sparking further battles with the Indigenous, and to limit the potential importation of mutinous slaves), the settler population felt they had no other option but to take up arms against their colonial matriarch. Earlier, when it came to defending their colonies from attacks from France and Spain, these same settlers were more than happy to let the British Red Coats do all the fighting. Now, when it appeared Britain might possibly halt the expansion of slavery to the west, they were more than willing to lay their lives down for the cause. What began as a small and in many ways elite rebellion was greatly (and unintentionally) aided by an edict delivered in November, 1775 by the Royal Governor of the British Colony of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, promising to emancipate and provide arms to any enslaved African who would desert his master and join Dunmore’s newly-formed contingent for the purpose of crushing the white settler rebellion. According to historian Graham Russell Hodges, Dunmore’s edict “did more than any other British measure to spur uncommitted white Americans into the camp of rebellion”, especially after more than 200 Africans immediately responded to Dunmore’s edict by risking their very lives to run away and join the Virginia governor’s fighting force. For this, Lord Dunmore was designated public enemy #1 by the white rebellion who burned him in effigy as far south as the Carolinas and as far north as Rhode Island. A Maryland preacher who would eventually become known as one of the so-called “founding fathers” named Patrick Henry railed against Dunmore from the pulpit for “tampering with our Negroes” and “enticing them to cut their masters’ throats while they are asleep.” He pondered how “men noble by birth and fortune should descend to such ignoble base servility.” [Horne, p. 224-225; 323.]

The colonial New England elite, among them “founding” slave-owners such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin and John Adams, were able to successfully ensure that those they viewed as part of the lower or peasant classes would make up the foot soldiers in their war against Britain by instilling in them a sense of overwhelming patriotism, framing the fight as one for freedom as opposed to tyranny. Understandably, the Africans in this war “almost universally sided with England and were hoping for an English victory, which they believed would deliver them from slavery.” In actuality, the American “Revolutionary” War was fought on the American side for the benefit of wealthy proprietors, landowners and plantation masters. What the lower class whites got out of this was the establishment of a regime they believed would preserve the doctrine of white supremacy for all eternity. That this so-called “revolution” was never intended to establish a democracy for anyone other than the minority ruling elite is apparent from the way the electoral process was set up and the ways in which it is controlled by those with the most money to spend, up to the very present.

Notes:

* The hatred that white people have historically and in fact continue to have for Black Americans is very much rooted in the latter’s resistance to slavery. Hatred for Black people was not the cause of slavery, at least not initially. The extreme antipathy is a result of the resistance to being enslaved on the part of Africans. The constant rebellion and acts of mutiny that comes with the territory of trying to enslave and oppress an entire race of people puts a deep fear into the hearts of the oppressor, and fear more often than not morphs into hatred. Living in constant fear and dread over when the next potential rebellion or insurrection was going to break out caused the white population to become even more vicious, brutal and oppressive in their tactics. In other words, had Black people (or the Indigenous) simply submitted to slavery and subordination (which no self-respecting people will ever do), the vicious amount of hatred whites developed for Black people would likely not have been as intense. Whites would have been content and happy were Africans to accept a status of inferiority, had they simply resigned to being enslaved, and in later eras segregated and ‘Jim Crowed’. But Black people did not and never will accept that, and thus the doctrine of white supremacy is still prevalent among the white population. This is not to say that racism only manifests itself in forms of antipathy. There’s also the false belief on the part of all too many whites that white people are in fact superior to non-white people. This belief emerged from the very act of enslavement itself, not the reaction to it on the part of the enslaved. After all, in order to consciously set out to enslave and degrade another human being (or class of human beings), one must convince himself that the one he is subjugating is his inferior in order to justify such cruelty.

Brilliant read…. “The constant rebellion and acts of mutiny that comes with the territory of trying to enslave and oppress an entire race of people puts a deep fear into the hearts of the oppressor, and fear more often than not morphs into hatred. Living in constant fear and dread over when the next potential rebellion or insurrection was going to break out caused the white population to become even more vicious, brutal and oppressive in their tactics.”

I think it was too easy here in Oz….and of course as a penal colony, with a difference of centuries and a hunter gatherer indiginous population…so what do we have in common with the US? A history of lies a spin off of white imperialism and a country full of fear that someone else wants to take what we essentially plundered and stole in the first place?

Exactly! In such a way, places like the United States, Australia, Israel and the former South Africa are kindred spirits! (Those are the four I can think of right off the top of my head though I’m sure I’m missing some.)

You guys always forget Canada …😉

Strange days in Darwin Caleb. US Navy in town very reserved. Marine presence growing I really wonder what the response of both black and white US military is, particularly to what they see of our very visible homeless often drunken indiginous on the srreet in the ‘city’ (2 streets 10 backpacker hostels and 50 watering holes)

Omg I’m so sorry! How is it that I could forget about Canada?! The plight of the Indigenous in Canada is as severe in the U.S. and somehow it is always overlooked in the media. Many like to think of Candada being “progressive” because of its health care system but in reality it is as much a project of imperialism and colonialism as the rest of them. And of course Alaska as well.

Great review. A recent talk Horne gave discussing his book is also excellent: http://stuartjeannebramhall.com/2015/07/11/the-real-cause-of-the-revolutionary-war-preserving-slavery/

I finally understand for the first time why the US ruling elite is so perversely greedy and mean-spirited. When a country is founded primarily to preserve the abominably profitable institution of slavery, this tends to dictate the standards and values employed to dictate the framework and direction on which its political policies will be based.

Indeed ms. Hall, I’d say it’s as bad and in many ways worse than it started out as, seeing as how the U.S. system and its values have truly spread to all corners of the earth.

Yes more about economics and capitalist profit than high ideals.

Absolutely. It was a transition from one form of tyranny to another, but with different titles.

There has been a lot of posts recently by different blog authors on how artfully the words slave and slavery were left out of the Constitution yet still codifying the legitimacy of the institution. I would think that at least Adams and Franklin would have black servants as opposed to slaves. Do you recall any info re that?

Realpolitik: I think the term was originated by Bismarck. At the end of the day governments have to balance the budget or get out of office. As they have wasted a lot through incompetence, and spend a lot on themselves, the only recourse is to despoil some group in the community with little political clout. Take Hitler: he inherited a bankrupt treasury, but offered full employment to Germans. How did he do it? The Jews of Germany made an involuntary contribution. This is what governments do. They target groups like ethnic minorities, the elderly and the disadvantaged, and move funds that should be spent on these groups to where it can reflect credit on themselves. And the voters do what they’re told. Americans are good at public relations. So good they often mistake the advertisement for the product. So do we all.

•You’ve identified one call to idealism here with a hidden profit motive, one I had no idea of. Economic autonomy and development of industry through cheap slave labour was advertised as a “war of independence from Britain”;

• the plantation system of course, the vaunted civilisation of the gentry of the Southern states, was founded on the slave trade, a 200 year reign of terror that destroyed the lives of seven million people from Africa;

• Then there’s the genocide of South American natives and the vandalising of their cultures by the Spanish which was advertised as a conversion to Christianity of heathen peoples for the glory of the Church;

• In Ireland, a system of absentee landlordism masked the genocide of the Irish people via typhus, cholera and starvation (The Great Hunger, Cecil Woodham Smith. Harper 1962) so the British could occupy the land;

• In London the rising crime rate was masked by an inefficient terrorist transportation system to Van Dieman’s Land (The Fatal Shore, Robert Hughes. Knopf 1986);

• The occupation of new lands in the Pacific and the so called bringing of civilisation and Christianity to ignorant savages masked destruction of native cultures there through disease and displacement (The Fatal Impact by Alan Morehead. Harper 1987);

• The “opening of the West”, the subject of innumerable films, really meant the planned genocide of the American native peoples whose land was being invaded (Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown. Holt, 1970); and the same in Texas and New Mexico as far as the Spanish people were concerned;

• The achievement of “crossing the continent (by railway)” was possible only through the exploitation of Chinese Coolie labour, many of whom died in the attempt *(and whose employment was a continuation of slavery with a different nationality);

• World War I, the “war to end all wars” really meant the carve up of the Ottoman Empire by the West;

• World War II, “the fight for democracy” really meant the establishment of American economic dominance in Europe and the Pacific, the founding of the American Empire;

• Intervention in South America against socialist governments through the 70s and 80s was made for the benefit of American companies who paid the US government liberally for ‘concessions’ there;

• World peace (except for the Korean War, the Vietnam War etc etc) was achieved by dropping the atom bomb at the end of WWII. Most people don’t seem to know that the effects of that 1945 explosion are still with us;

• Poke around in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars and you will uncover a fight to retain control of essential (it is thought) oil supplies needed by American companies.

This unconsidered rave is made in support of what you are attempting here, the education of citizens some of whom are quite comfortable with their head in the sand thanks very much. My conclusion is, never trust a man waving a flag, someone who knows all the words to a national anthem or can sum up the cause of a war in a phrase.

Wow. Your comment is worthy of a blog post all in itself, with so many examples of the perilous destruction that is an essential part of imperialism. The amount of money that has been looted from African people for almost half a millennium cannot even be calculated! And to think how people continue to be brainwashed by their own government and media that somehow Africans are somehow “unworthy” of being in the least bit compensated in any way, shape or form!

Reblogged this on The Militant Negro™.

Reblogged this on It Is What It Is and commented:

What’s behind the “War for Independence”?